Nurse Alters Morphine Record, Patient Dies: CNO Orders Permanent Resignation

A Profound Breach of Trust in End-of-Life Care In CNO v. Lindsey Coyle, the Discipline Committee of the College of Nurses of Ontario addressed one

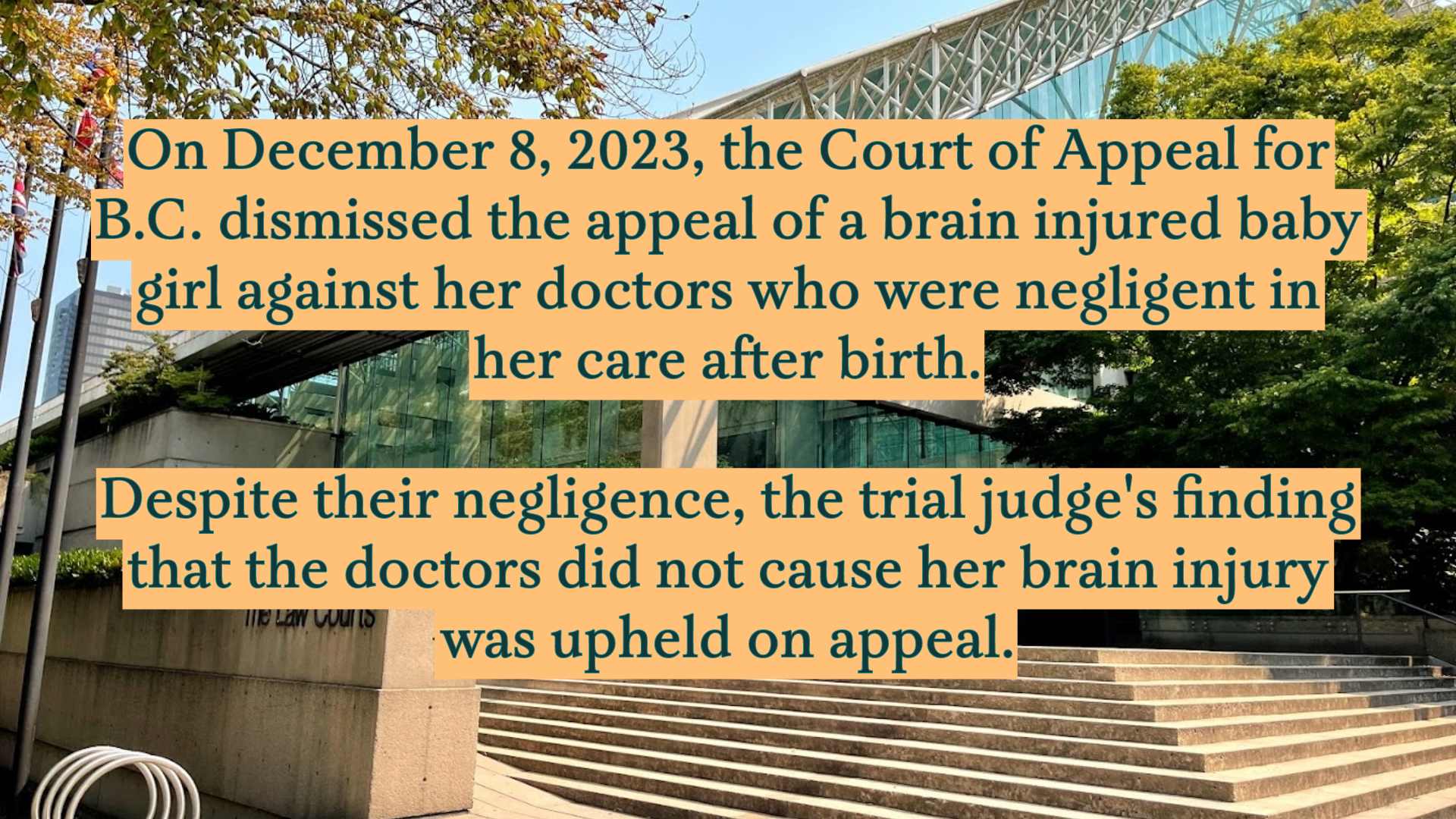

On December 8, 2023, the Court of Appeal for British Columbia dismissed the appeal of a brain injured baby girl (“Kyrcee”) against her family physicians who were found to be negligent in her care in the days after her birth.

Although the trial judge had found that the family physicians had breached the standard of care by failing to monitor the baby’s condition in the days following her birth to assess the need for a follow-up bilirubin test, the Court did not accept that there was any causal connection between their negligence and the brain injury suffered.

ISSUE

The issue on appeal was whether the trial judge erred in his causation analysis.

First, relying primarily on Snell v. Farrell, 1990 CanLII 70 (SCC), [1990] 2 S.C.R. 311 and Benhaim v. St-Germain, 2016 SCC 48, the Appellant submits the trial judge erred by failing to consider whether it was appropriate to draw an adverse inference of causation in circumstances where causal uncertainty was attributable to the Respondents’ negligence.

Second, the Appellant argues that the trial judge misapprehended evidence material to the issue of causation.

FACTS

Kyrcee was born on July 29, 1996, slightly pre-term. She was discharged from the hospital two days later. She suffered life-altering injuries attributable to neurotoxic levels of bilirubin discovered upon her re-admission to the hospital on August 6, 1996.

Bilirubin is a yellowish chemical by-product of the natural breakdown of red blood cells. The liver processes bilirubin from the bloodstream and releases it into the intestinal tract to be excreted. Newborns typically have increased red blood cell turnover and still-maturing livers that struggle to process bilirubin quickly enough, causing an increase in serum bilirubin concentration. In some cases, this imbalance between an infant’s bilirubin production and the ability to eliminate it from the bloodstream results in hyperbilirubinemia, which manifests as a yellowing of the skin and eyes, commonly known as jaundice.

Physiologic jaundice is a normal occurrence in many infants due to the increased breakdown of red blood cells in the first week after birth. It develops in approximately 50% of term babies and is somewhat more common in pre-term neonates. Jaundice serves as only a very rough indicator of bilirubin levels and typically becomes apparent at bilirubin levels of 85–120 µmol per litre. As bilirubin levels rise, an infant’s jaundice will deepen in colour and spread from the head down the body. Physiologic jaundice usually resolves on its own as the infant’s liver matures and becomes more effective in processing bilirubin. In pre-term infants such as Kyrcee, it typically peaks and plateaus within the first five to seven days of life and poses no harm.

In rare instances, a significant imbalance in an infant’s bilirubin production and elimination can cause the buildup of bilirubin in the bloodstream to cross the blood-brain barrier and cause damage to the infant’s brain, resulting in acute bilirubin encephalopathy. The symptoms of acute bilirubin encephalopathy include lethargy, refusal to feed, high-pitched crying, severe back arching, seizures and apnea. This acute condition can progress to chronic bilirubin encephalopathy, characterized by irreversible brain damage—or kernicterus—as a result of the bilirubin neurotoxicity.

Kyrcee’s bilirubin level was measured on July 31 before she was discharged from the hospital. It was not at a level requiring phototherapy—the first-line treatment for reducing hyperbilirubinemia in infants.

She was examined by Dr. Brian Ewart on August 1, 1996—three days after her birth and the day after her discharge from hospital. While Dr. Ewart noted Kyrcee to be “icteric” (jaundiced), no future appointment was scheduled to monitor her condition, and no follow-up bilirubin test was ordered.

The trial judge found that, in light of Kyrcee’s elevated risk profile for hyperbilirubinemia and evident jaundice about 38 hours after her birth, the respondents failed to meet the standard of care expected of them by, among other things, failing to monitor her condition in the days following her birth and discharge from the hospital to assess the need for a follow-up bilirubin test.

The issue at trial then became whether the Respondents’ negligence caused Kyrcee’s injuries.

Kyrcee’s bilirubin level was not measured again until her re-admission to the hospital on August 6, when she was in distress and displaying classic symptoms of acute bilirubin encephalopathy. Sadly, Kyrcee’s high bilirubin levels led to the development of kernicterus and, despite prompt medical intervention, the injuries she suffered could neither be avoided nor reversed.

Because she was not tested after July 31, Kyrcee’s bilirubin levels between August 1 and August 5 are unknown. In addition, the etiology of the hyperbilirubinemia Kyrcee experienced in the days following her birth could not be definitively determined.

On causation, the parties, through their respective expert witnesses, presented two competing theories concerning the likely trajectory of Kyrcee’s rising bilirubin levels between July 29 and August 6 and why she developed acute bilirubin encephalopathy.

Kyrcee’s primary expert witness on causation, Dr. Kaplan, posited a pathologically abnormal, progressive, and essentially linear increase in her bilirubin levels from birth to her re-admission to the hospital eight days later. He opined that, had appropriate action been taken following Kyrcee’s discharge from the hospital, the severe hyperbilirubinemia and resultant bilirubin neurotoxicity would have been avoided.

The Respondents’ expert witnesses on causation, Dr. Boulton and Dr. Van Aerde, opined that it was far more likely, if not certain, that there was a biphasic trajectory of bilirubin in Kyrcee’s system, not a linear one. In their view, while there was an initial, normal and physiological rise in bilirubin that plateaued in the days following Kyrcee’s discharge from the hospital, this was followed by a massive and unpredictable oxidative hemolytic event that likely began about 24 hours before her re-admission to the hospital on August 6. This event caused the rapid destruction of Kyrcee’s red blood cells resulting in acute anemia, severely elevated bilirubin levels and, ultimately, brain damage.

Drs. Boulton and Van Aerde agreed that, even if a follow-up bilirubin test had been ordered when Dr. Brian Ewart examined Kyrcee the day after her discharge on August 1, it would not have changed the outcome. Her severe hyperbilirubinemia was due to an acute oxidative hemolytic event of independent origin that arose several days after Kyrcee’s appointment with Dr. Brian Ewart. In other words, they opined that Kyrcee’s injuries were inevitable and would have been sustained without the defendants’ negligence.

The trial judge accepted the evidence of the respondents’ expert witnesses that Kyrcee’s bilirubin levels were the product of unrelated biphasic processes—one consistent with a predictable, physiological condition common to newborns, and the other attributable to an unrelated and wholly unpredictable oxidative event that caused Kyrcee’s bilirubin levels to spike on August 5.

The judge found as a fact that Kyrcee failed to demonstrate, on a balance of probabilities, that a follow-up bilirubin test ordered by the respondents before August 5 would have prevented her injuries. He accepted the evidence of Dr. Boulton that the sudden, oxidative hemolytic event that occurred shortly before her admission to hospital was an independent event—one so extreme that it would have overwhelmed the ability of any liver to process it.

In drawing this inference, the judge relied primarily on two considerations.

DECISION

The Appellant argued on appeal that:

The Court of Appeal rejected the first ground of appeal. In so doing, it determined that the trial judge was aware of the availability of an adverse causal inference discussed in Snell and Benhaim.

The Court of Appeal found that this case was distinguishable to Ghiassi given the substantial body of expert evidence called by both parties on the issue of causation. The judge reviewed this evidence at length, noting the extent to which it revealed weaknesses in the Appellant’s expert evidence relating to causation. The trial judge made factual findings that Kyrcee’s injuries were not caused by the Respondents’ negligence, but were more likely attributable to a later-arising independent event.

The trial judge concluded that a follow-up bilirubin test shortly after Kyrcee’s discharge from the hospital would not have prevented her injuries.

The Court of Appeal found it implicit in the reasons that the trial judge, in the exercise of his discretion and having regard to the factual findings he made, understandably declined to draw an adverse causal inference.

The Court of Appeal saw no reviewable error in any of this. The trial judge’s factual findings were well grounded in the evidence.

With respect to the second ground of appeal, broadly, that the trial judge erred by misapprehending evidence material to the causation analysis, the Court of Appeal was not persuaded that the trial judge ignored the evidence of Kyrcee’s worsening jaundice in his causation analysis.

According to the Court of Appeal, the trial judge placed significant weight on the absence of any behavioural symptoms that would likely have become apparent well before August 6 on Dr. Kaplan’s progressive, linear theory. The trial judge was entitled to approach the case with the obvious disconnect between Dr. Kaplan’s theory and Kyrcee’s behaviour in mind. He was also entitled to have regard to the totality of the expected symptoms associated with severe hyperbilirubinemia, rather than assign the fact of progressing jaundice dispositive weight. The Court of Appeal accepted that this choice was squarely within the trial judge’s discretion as the trier of fact and saw no basis to interfere with it.

For these reasons, the appeal was dismissed.

Decision Date: December 8, 2023

Jurisdiction: Court of Appeal for British Columbia

A Profound Breach of Trust in End-of-Life Care In CNO v. Lindsey Coyle, the Discipline Committee of the College of Nurses of Ontario addressed one

What College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario v. Thirlwell, 2026 ONPSDT 5 Means for Patients and Public Trust In College of Physicians and Surgeons